Your graphic novel is not about an asylum seekers centre, about asylum community centres. Can you explain what this concept entails?

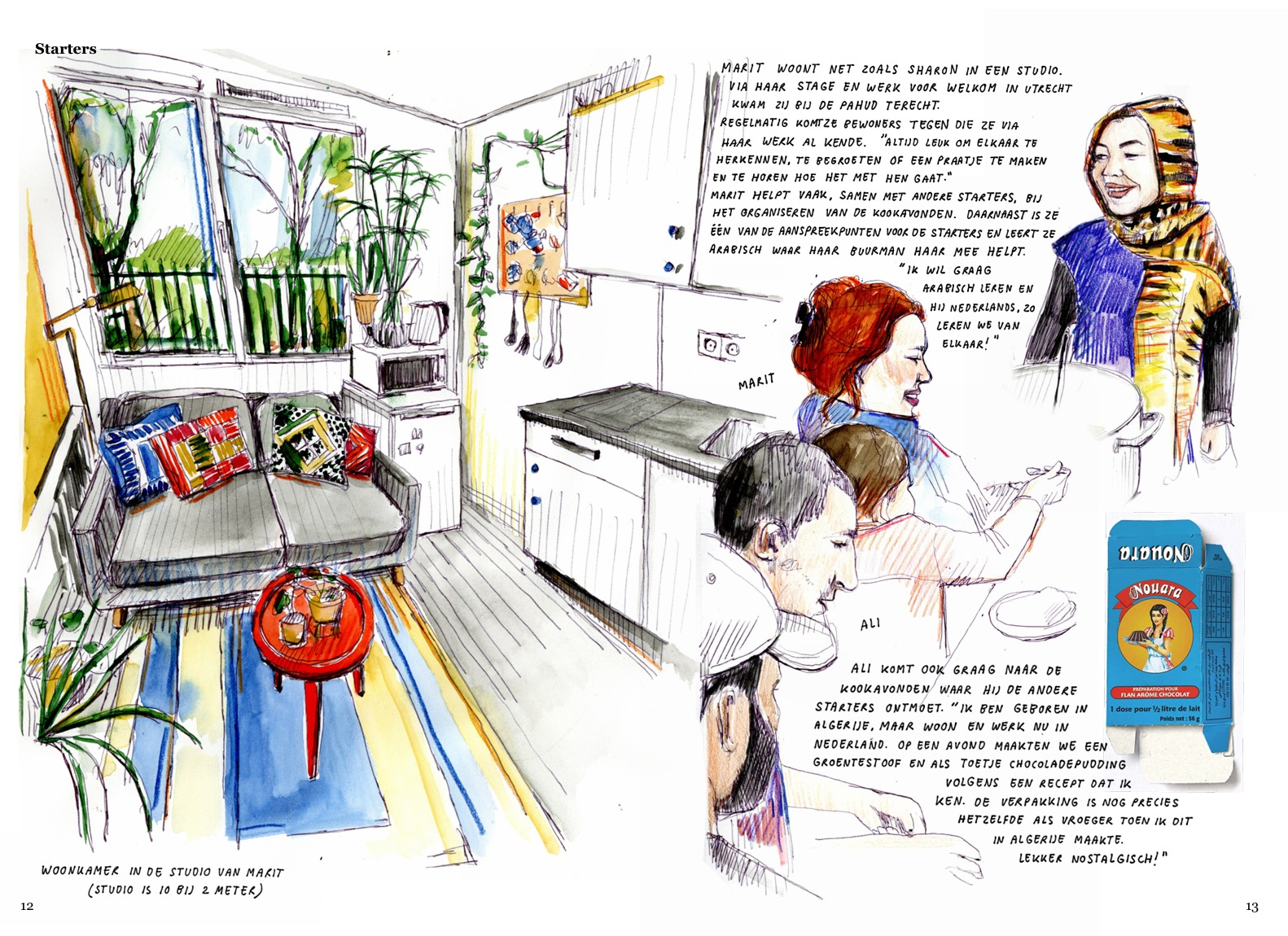

‘The asylum community centres are a new concept and unique for the city of Utrecht. These centres are not just open to the residents of the nearby asylum seekers centres, but to all locals in the neighbourhood and in Utrecht. They are home to all sorts of activities that help people get to know the city, learn Dutch or English, or just get together and cook, do a dance workshop, or anything at all. They are an initiative from the so-called Plan Einstein: a project from the City of Utrecht to support the integration of immigrants into society and the city. They key word in the centres is ‘togetherness’: everyone is welcome to step inside, to just drop by or organise an activity themselves.’

How did you get involved in this? Did you simply approach the local government and said: I’m going to make a graphic novel about this! Or did they ask you?

‘It all happened quite gradually. When I finished my Illustration studies, I was already working with graphic journalism. One time I organised a workshop in a former care home, where young people and the elderly live together side by side – and where I’ve been living myself since then. The purpose was not to teach people how to draw, but simply to use drawing as a way to connect to each other. It was subsidised by culture platform ZIMIHC and The Social Collective, who in turn were also involved with these asylum community centres. And through them, I came into touch with the Plan Einstein project.’

So your graduation project was what got the ball rolling in this direction?

Well, it actually started earlier. Already in the third year of study, and during my internship at the Dutch newspaper NRC, I knew where I wanted to go with my makership. As a student, you are often still looking for directions: who are you and what do you want to create? For me, the answer turned out to be graphic journalism. And also that I want to use my art as a means of connecting people. From that moment, things started to take shape. I created and published an illustrated newspaper about the mixed care home. And next, my contacts from The Social Collective suggested that the asylum community centres would also suit the way in which I visualised people and their stories. And so they asked me if I was interested to make this graphic novel…’

What kinds of people and stories did you encounter there?

‘I mainly tried to capture the atmosphere at the locations themselves. I went to visit regularly for about a year, just drop by spontaneously at various moments. When I came to help in the kitchen on Monday, there would be someone asking me to come on Friday as well. “You can come and play music with us!” The laundry room turned out to be a nice place to talk to people. Everyone has to do the laundry from time to time, so the moments spent waiting there provided lots of room for conversation. And so I just went along with the flow of the people living there.’